This is a re-post that was originally part of the 2014 book release blog tour, hosted by Sirens of Suspense (RIP).

Thank you, Sirens of Suspense, for the opportunity to drop by on my February blog tour for The Kept Girl, a novel of 1929 starring the young Raymond Chandler, his devoted secretary and the real-life cop who is a likely model for Philip Marlowe.

With this guest post, I'd like to send a little virtual love note out to the used bookshops of the world—the long, narrow ones with high shelves and dust and cats and grumpy clerks and little stashes of rarities that some poorly-behaved customer has tucked away behind the automotive repair guides with the vague intent of purchasing when their monthly check arrives.

There aren't very many used bookshops left these days, and I think we should all strive to patronize the ones that are still hanging on. The internet has democratized the book collection hobby, making it all too (relatively) cheap and easy to amass every Dell map back mystery, or those sly Edward Gorey Anchor Books paperbacks, or whatever special patch of print history it is that makes your pulse race.

But the downside of the internet is that, while it's very good at delivering the things one already knows they're interested in, it tends to run thin in true surprises.

And it's those true surprises, jaw droppers and head shakers, in which the best bookshops have ever traded, and that make them such valuable spaces in our shared cultural life.

Take, for example, the one rare little document that gave off the sparks that burned and flared into my debut novel, The Kept Girl.

I didn't even find it myself. My '90s zine pal Lynn Peril of Mystery Date fame–that's her on the cover of the RE/Search book Zines! Vol. One–was roaming the aisles of Kayo Books in San Francisco's Tenderloin, a paperback collectors' store specializing in pulp exploitation and oddities, when she noticed a slim pamphlet tucked up on a shelf. Even before picking it up, she could see it was too thin to be a mass market title, and the wrong size for a cheap recipe book. There was no writing on the spine, there wasn't even a spine. It was something unique, a one-off. Curious, she picked it up.

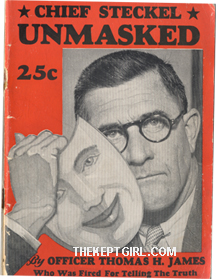

Los Angeles crime lore isn't really Lynn's beat, but for $5, Chief Steckel Unmasked (originally priced at 25¢, with the penciled notation "Read and pass on") was too interesting to leave behind. She bought it, took it home, and some time later asked me if I'd like to see it. Would I!

Chief Steckel Unmasked is one incredibly peeved ex-cop's and Police Commission investigator's cry into the darkness of a sun-drenched city gone foul to its roots. He names names, calculates illegal profits, gives the addresses of whole streets packed with houses of ill fame, and ultimately calls on the righteous population of Los Angeles to rise up and reclaim their community from the elected gangsters that control it.

Reading it, I felt a weird twinge. Los Angeles crime lore is my beat, but I'd never heard of this guy. Yet he seemed to know where all the bodies were buried, and to be completely fearless. I turned to the historic Los Angeles Times archives, where a rich history revealed itself.

Thomas H. James was a the foster son of a wealthy leader of the Women's Christian Temperance Union. He went into police work to help his fellow man, and campaigned for Mayor Porter, impressed by promises of reform. Porter won, and installed Tom James as his personal police commission investigator.

Disillusioned at the state of the city, and to by Porter's true colors, James started preaching reform. They bounced him down to beat cop at a busy downtown intersection. He didn't stop. They sent him into the deep San Fernando Valley, where the chicken ranchers were. He kept squawking. They fired him, and he wrote and published this little book, sued to get his job back, and within a decade saw the recall of crooked Mayor Frank Shaw. (The reform of the LAPD would take a little longer.)

Aspects of Tom James' life and character reminded me strongly of Raymond Chandler's white knight detective Philip Marlowe. After leaving City Hall under a cloud, uniformed James preached reform two blocks east of Chandler's oil company offices, and was the talk of the town in 1929. Later, James was enmeshed in a notorious shooting that Chandler would fictionalize in the transitional Black Mask story "Spanish Blood." Could Chandler, who drew on real crimes for his plots and real buildings for his scenes, have looked to a real reformer when creating his detective hero?

That idea was the spark that would burn and flare, as more research was packed around it, until I saw a way to tell Tom James' fascinating story, and the young Chandler's, and that of the sad and deluded people who fell victim to a strange cult of angel worshippers called The Great Eleven, all in one neat little mystery.

As the puzzle pieces came together, I leaned in and tucked them in tighter. It felt kind of magical, as if the story was meant to be told just this way. And it's a book that might never have happened had my friend not spied that odd little pamphlet on the shelf and passed it on.

So let's hear it for those wonderful used bookshops, where surprises lie in wait until the right person comes along and notices them. Long may they trade!